Gerrymandering Is The Drawing Of Which Of The Following?

After the Census Bureau releases detailed population and demographic information from the 2020 census on August 12, states and local governments begin the one time-a-decade process of describeing new voting commune jumparies known every bit redistricting. And gerrymandering — when those boundaries are drawn with the intention of influencing who gets elected — is bound to follow.

The current redistricting bicycle will be the first since the Supreme Court'southward 2019 ruling that gerrymandering for party advantage cannot be challenged in federal court, which has prepare the stage for peradventure the most ominous round of map describeing in the country's history.

Here are 6 things to know most partisan gerrymandering and how information technology impacts our democracy.

Gerrymandering is securely undemocratic.

Every ten years, states redraw their legislative and congressional district lines following the census. Because communities change, redistricting is critical to our democracy: maps must be redrawn to ensure that districts are as populated, comply with laws such as the Voting Rights Human activity, and are otherwise representative of a state's population. Washed correct, redistricting is a chance to create maps that, in the words of John Adams, are an "verbal portrait, a miniature" of the people as a whole.

Only sometimes the process is used to depict maps that put a pollex on the scale to manufacture election outcomes that are discrete from the preferences of voters. Rather than voters choosing their representatives, gerrymandering empowers politicians to choose their voters. This tends to occur especially when linedrawing is left to legislatures and one political party controls the process, as has become increasingly mutual. When that happens, partisan concerns almost invariably take precedence over all else. That produces maps where electoral results are virtually guaranteed even in years where the party depicting maps has a bad year.

There are multiple ways to gerrymander.

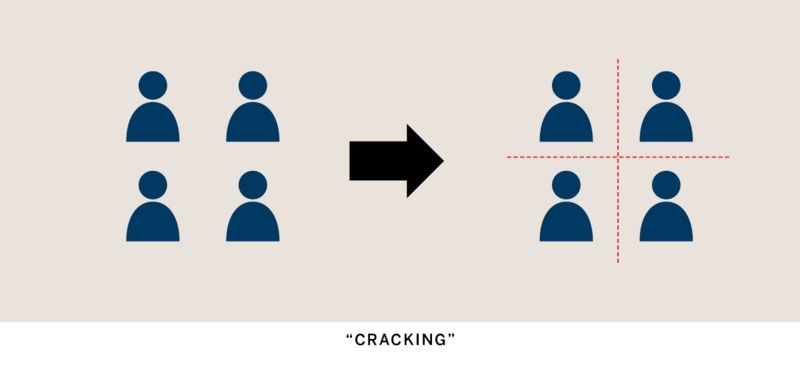

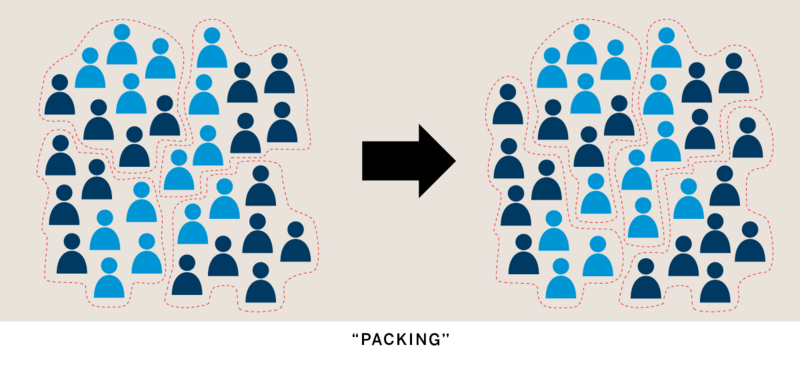

While legislative and congressional district shapes may look wildly different from state to state, most attempts to gerrymander can best be understood through the lens of ii basic techniques: fissureing and packing.

Scissureing splits groups of people with similar charair conditioningteristics, such equally voters of the same party affiliation, across multiple districts. With their voting force divided, these groups struggle to elect their preferred candidates in whatsoever of the districts.

Packing is the opposite of scissureing: map describeers cram certain groups of voters into every bit few districts as possible. In these few districts, the "packed" groups are likely to elect their preferred candidates, but the groups' voting strength is weakened everywhere else.

Some or all of these techniques may be deployed by map drawers in order to build a partisan advantage into the jumparies of districts. A key note, however: while sometimes gerryhomodering results in oddly shaped districts, that isn't always the case. Clefting and packing can frequently result in regularly shaped districts that wait entreatmenting to the heart but nonetheless skew heavily in favor of one party.

Gerrymandering has a real impact on the balance of power in Congress and many state legislatures.

In 2010, Republicans — in an endeavour to control the drawing of congressional maps — forged a campaign to win majorities in as many land legislatures as possible. It was wildly successful, giving them command over the depicting of 213 congressional districts. The redrawing of maps that followed produced some of the most extreme gerrymanders in history. In battlefooting Pennsylvania, for instance, the congressional map gave Republicans a virtual lock on 13 of the country'south 18 congressional districts, even in elections where Democrats won the majority of the statewide congressional vote.

Nationally, extreme partisan bias in congressional maps gave Republicans a net 16 to 17 seat advantage for near of concluding decade. Michigan, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania alone — the three states with the worst gerrymanders in the terminal redistricting wheel — accounted for 7 to 10 actress Republican seats in the Firm.

On the state level, gerrymandering has besides led to significant partisan bias in maps. For example, in 2018, Democrats in Wisconsin won every statewide function and a majority of the statewide vote, merely thanks to gerrymandering, won only 36 of the 99 seats in the state assembly.

Though Republicans were the primary beneficiaries of gerrymandering last decade, Democrats take also used redistricting for partisan ends: in Maryland, for example, Democrats used control over map-describeing to eliminate 1 of the state's Republican congressional districts.

Regardless of which party is responsible for gerrymandering, it is ultimately the public who loses out. Rigged maps make elections less competitive, in turn making even more Americans feel like their votes don't affair.

Gerrymandering affects all Americans, but its most significant costs are borne by communities of color.

Residential segregation and racially polarized voting patterns, especially in southern states, mean that targeting communities of color can be an eventive tool for creating advantages for the party that controls redistricting. This is truthful regardless of whether information technology is Democrats or Republicans drawing the maps.

The Supreme Court's 2019 decision in Rucho v. Common Cause greenliteing partisan gerryhuman beingdering has made things worse. The Voting Rights Act and the Constitution prohibit racial discrimination in redistricting. But because at that place frequently is correlation between party preference and race, Rucho opens the door for Republican-controlled states to defend racially discriminatory maps on grounds that they were permissibly discriminating against Democrats rather than impermissibly discriminating against Black, Latino, or Asian voters.

Targeting the political power of communities of colour is too often a key chemical element of partisan gerrymandering. This is especially the case in the South, where white Democrats are a comparatively small part of the electorate and oft live, problematically from the standbetoken of a gerryhumanderer, very close to white Republicans. Even with slicing and dicing, discriminating against white Democrats but moves the political dial and then much. Because of residential segregation, it is much easier for map depicters to pack or scissure communities of color to reach maximum political advantage.

Gerrymandering is getting worse.

Gerrymandering is a political tactic nearly as old equally the U.s.a.. In designing Virginia's very kickoff congressional map, Patrick Henry attempted to draw district boundaries that would block his rival, James Madison, from winning a seat. Merely gerryhuman beingdering has also changed dramatically since the founding: today, intricate computer algorithms and sophisticated data about voters allow map depicters to game redistricting on a massive scale with surgical precision. Where gerrymanderers one time had to selection from a few maps fatigued by paw, they now can create and selection from thousands of estimator-generated maps.

Gerrymandering too looks likely to go worse considering the legal framepiece of work governing redistricting has non kept upwardly with demographic changes. Before, most people of color in the country'due south metro areas lived in highly segregated cities. Today, notwithstanding, a majority of Black, Latino, and Asian Americans live in diverse suburbs. This change has given rise to powerful new multiracial voting coalitions outside cities such as Atlanta, Dallas, and Houston that accept won or come close to winning power. However the Supreme Court has non granted these multiracial coalition districts the same legal protections as majority-modestity districts, making them a key target for dismantling by partisan map drawers.

Federal reform can assistance counter gerrymandering — merely Congress needs to human activity before long.

The For the People Deed, a countrymark slice of federal democracy reform legislation that has already passed the House, represents a major step toward adjourning political gamesmansend in map drawing. The nib would enhance transparency, strengthen protections for communities of colour, and ban partisan gerrymandering in congressional redistricting. It would likewise improve voters' ability to challenge gerrymandered maps in court.

With redistricting at present beginning in many states, the need for Congress to pass reform legislation is more urgent than ever. Unless that happens, we chance another decade of racially and politically discriminatory line-drawing. But time is running brusque. The Demography Agency released data to the states for redistricting on Baronial 12. If new laws are to have the maximum bear upon, Congress needs to act quickly. Fair representation depends on it.

Source: https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/gerrymandering-explained

Posted by: stevensonnotheires.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Gerrymandering Is The Drawing Of Which Of The Following?"

Post a Comment